Marlo Thomas and the children of Free To Be writers, performers, and friends, 1974. Courtesy of Marlo Thomas.

Free to Be You and Me. . . at 50

In 1971, the actress Marlo Thomas—already famous for her role as a spirited, single woman on the hit sitcom “That Girl”—was searching for new children’s books to read to her young niece, Dionne. In particular, she was looking for stories that harmonized with the liberal feminism fueling the consciousness-raising sessions and ERA marches that increasingly filled her calendar. The pickings were slim. As Thomas later recalled, “the books all told the same old stories, starring the same old prince, promising the same old happy ending. None of them had any new ideas that would encourage Dionne to dream her own dreams.” So she decided to create something herself. Leveraging her connections in the entertainment industry, and consulting with activists (including “Ms.” magazine founders Gloria Steinem and Letty Cottin Pogrebin) she assembled a team of collaborators to produce an album that would counteract stifling gender stereotypes. The result was “Free to Be…You and Me,” a collection of original songs, stories, and skits first recorded as a vinyl LP in 1972 and followed by a printed book and television special in 1974.

Laurie Glick, Illustration for Free to Be…You and Me record cover. © 1972, Free To Be Foundation, Inc. Used by permission.

By almost any measure, this groundbreaking trio of children’s media was a rousing success. With a catchy soundtrack recorded by celebrated musicians, actors, and singers, “Free to Be…You and Me” wasn’t just an appealing novelty for the elementary-school set. Offering a fresh alternative to prevailing norms, it changed the way in which audiences thought about acceptable behavior for boys, girls, men, and women. Using popular media to inspire and influence young people—as well as the adults who cared for them—it animated a particular vision of social change rooted in the Civil Rights and women’s liberation movements of the 1960s and early 70s. The time was ripe for Thomas’s intervention. Selling over 500,000 copies in the first few years, the album was gilded a “Gold Record” and garnered a Grammy nomination. Collectively, the album, book, and TV broadcast reaped Emmy and Peabody awards, among other accolades.

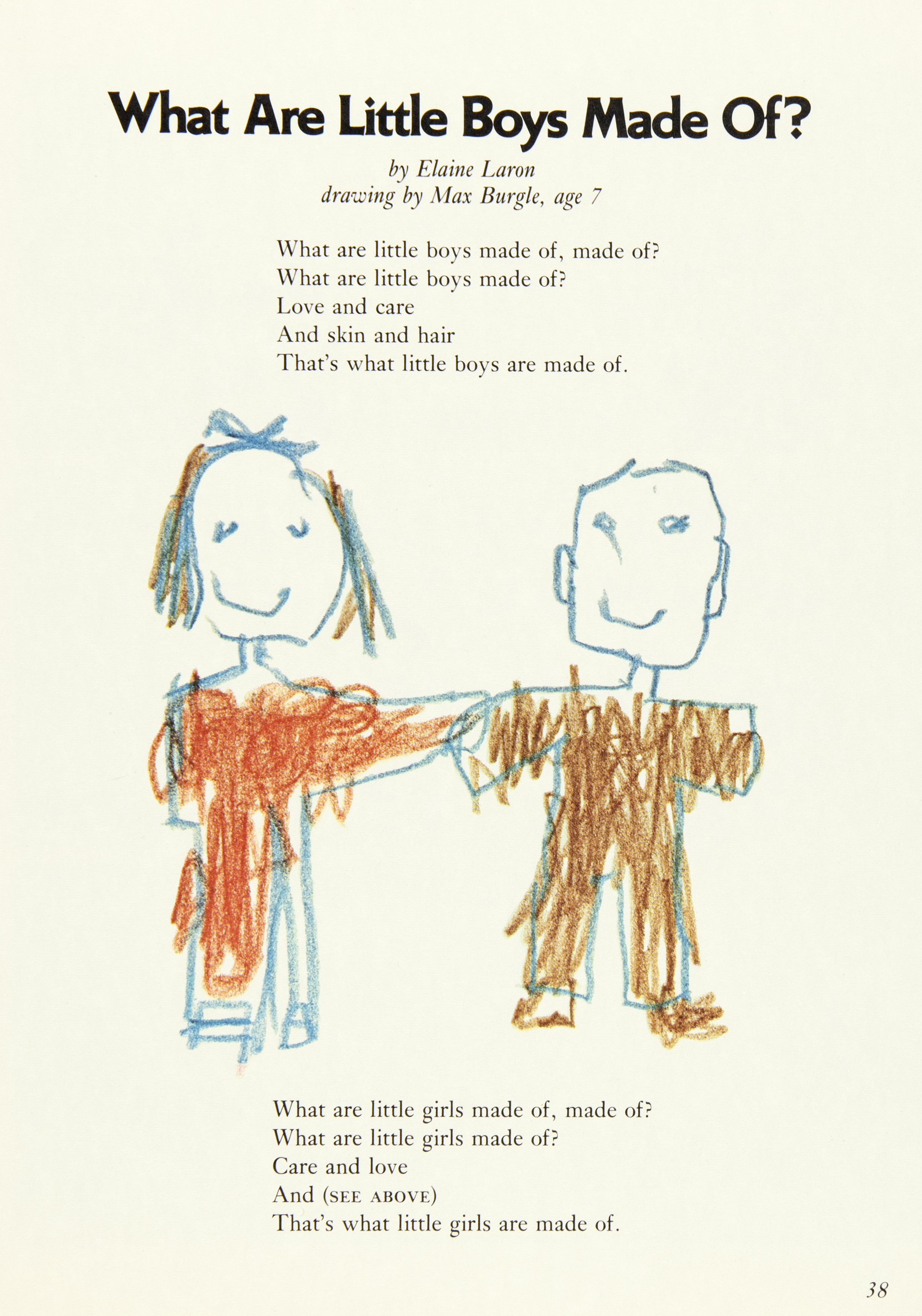

Along with hula hoops and mood rings, the first generation of “Free to Be” kids grew up belting out tunes titled “William’s Doll,” “Parents Are People,” and “It’s All Right to Cry.” Infused with positive messages valuing cooperation, free expression, and respect for diversity, “Free to Be” taught children to resist blind conformity to certain kinds of social expectations. The title track, performed by the British pop band the New Seekers, beckoned young listeners into a future bursting with boundless possibility: “There’s a land that I see / Where the children are free. / And they say it ain’t far/ to this land from where we are.” Adding a feminist twist to notions of liberal individualism, personal autonomy, and self-actualization, the lyrics continued: “Every boy in this land / grows to be his own man. / In this land, every girl / grows to be her own woman.” The ballad “Parents are People” honored the care-work of mothering and fathering as well as paid work outside the home—by women and men alike. Girls would no longer limit their occupational aspirations to typically “feminine” jobs; they could become doctors, bakers, or sea captains. Boys would still play baseball and zoom around with toy trucks—but it was also OK for them to play with dolls and to cry shamelessly when they felt sad.

Growing up in a middle-class suburb of St. Louis, Missouri, I was five years old when the “Free to Be” TV special hit the airwaves. During grade school, I kept my “Free to Be” album on constant rotation, stashing my matching book under my bed for easy access. Decades later, after giving birth to my first child, a friend sent me a “Free to Be” CD as a baby gift, its hot pink record cover scaled down to fit the latest audio technology. Listening to the soundtrack felt like opening a buried treasure chest, but it wasn’t just nostalgia that tuned me in. My rediscovery led me to embark on a research project resulting in an anthology of essays on “Free to Be’s” historical significance. Along with my co-editor, I invited Marlo Thomas and her colleagues, as well as numerous writers, artists, and activists, to offer retrospective assessments of “Free to Be’s” creation, critical reception, and legacy.

On the eve of “Free to Be’s” 40th anniversary, Thomas’s niece Dionne reflected on the project’s emboldening influence. By then a television producer and mother of two sons, she recalled: “My aunt has always been ‘Free to Be’ in my eyes. I grew up feeling that I wanted to attack life in the same way. I knew that whatever dreams I had would be my own and not a product of what others wanted for me… As a young person, it left me feeling energized, transformed, and capable of taking on anything that might come my way.” As her tribute suggests, for countless girls, “Free to Be” served as an original primer of “empowerment feminism”—a strongly individualistic “be it all / have it all” ethos compatible with both traditional nuclear family life and neoliberal ideals of career success, corporate leadership, and personal advancement for women. For youth who came of age during the 1970s, the message that women could succeed by aiming high, working hard, and—as former Facebook executive Sheryl Sandberg famously put it “leaning in”—had yielded positive results for a select group of employed mothers in their quest to achieve parity in the workplace.

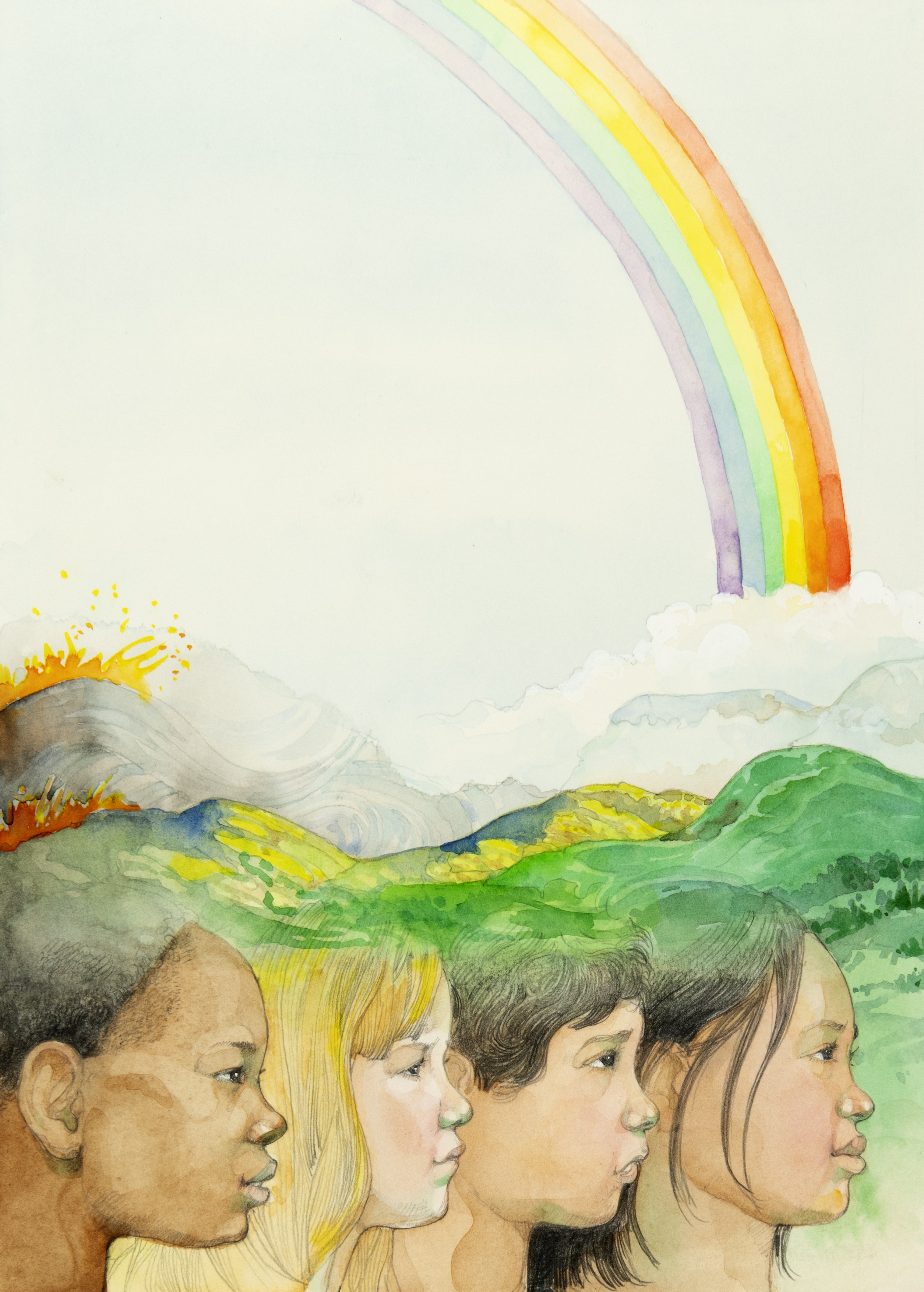

Barbara Bascove, Illustration for Free to Be…You and Me by Marlo Thomas & Friends (Running Press). Collection of the Norman Rockwell Museum. © 1974 Barbara Bascove.

To their credit, “Free to Be’s” creators knew that a change in mindset was only part of the solution. Tunes and tales combating sexism can only go so far. That’s why some of them also led political advocacy groups to help bring about systemic change. They also funneled “Free to Be’s” profits into a charitable foundation, which still benefits low-income and marginalized families today. With respect to racial and socioeconomic diversity, “Free to Be’s” creators attracted a demographically varied audience of youth, some of whom lived beyond the picket fences of the white middle class. (Here, they took a leaf from “Sesame Street’s” playbook, which transformed the children’s media landscape by targeting families in underserved, inner-city communities as well as suburbs.) While “Free to Be’s” writers and producers were all white, up-and-coming professionals in the television, theater, music, and publishing industries, when it came to casting performers, they contracted many African-American luminaries including Harry Belafonte, Diana Ross, Rosey Grier, and a 16-year old Michael Jackson to sing and act on recordings. They also commissioned an inspired appearance by the Voices of East Harlem, a community-based performance group that blended gospel, R&B, and soul styles in their stirring rendition of “Sisters and Brothers,” an anthem heralding unity and fictive kinship among children across racial, ethnic, and gender lines.

Max Burgle, Galley proof for Free to Be…You and Me by Marlo Thomas & Friends (Running Press). Courtesy of Laura Englander. © 1974 Max Burgle.

Boys who grew up with “Free to Be” also reflected on its impact. For lads who did not conform to dominant masculine ideals, the album provided an alternative, if still limited, manual of social acceptance. Although “Free to Be” never condoned or even acknowledged homosexuality, it comprised “a pebble of dissent in an ocean of gender conformity” that affirmed an emotional register of gentle tenderness in contrast to manly swagger and bravado. For its time, the song “William’s Doll” expressed a relatively radical notion: boys could adopt caregiving roles in doll play that had long been coded as female. “A doll, said William, is what I need / To wash and clean, and dress and feed / A doll to give a bottle to/ And to put to bed when day is through /And any time my doll gets ill / I’ll take good care of it / said my friend Bill.” Over the decades, many gay men told Marlo Thomas that the album had provided “the first inklings” of reassurance that they “were going to be okay” despite the homophobia swirling around them. Straight men, too, recounted finding in these lyrics permission to grow into nurturing fathers.

In 2022, 50 years since “Free to Be’s” creation, a fresh appraisal is timely once again. Noting the project’s ideological limitations and missteps (however well-intentioned) does not diminish its importance. After a half decade, it’s hardly shocking that some lyrics sound outmoded to contemporary ears: consider the proclamation in “Parents are People” that girls cannot grow up to be daddies, while boys can never mature into mommies. Although the 1970s spawned several works of anti-sexist children’s literature that affirmed non-binary gender identities, “Free to Be’s” creators assumed the existence of only two genders linked to biological sex at birth. With a few exceptions (including “Atalanta,” a feminist retelling of a Greek myth that celebrated female independence, intellect, and adventure) “Free to Be’s ”offerings reinforced pronatalist ideals and a traditional nuclear family structure. As one feminist critic noted at the time, “Nowhere are free and loving relations between two girls or two boys depicted; the fun is always shared by little [boy-girl] couples.” Furthermore, the album’s core assumptions about human potential were forged in a context of relative social and economic security. Capitalizing on advice to “be free” and “follow your dreams” is more readily achieved, or even attempted, by those whose lives are cushioned by tangible resources and other advantages. Despite its celebration of cultural diversity, “Free to Be” does not invite a deeper critique of wealth inequality, corporate power, or social policies that contribute to material hardships among families facing low wages, unemployment, food or housing insecurity, and rising costs of living.

Still, “Free to Be” was a bold, visionary project during its time. Various audiences have made sense of its material through different interpretive lenses. Precisely because of its progressive ethos—and its vibrant success in shaping hearts and minds—it invited backlash from quarters where it was deemed threatening to the status quo. The responses of listeners have shifted, too, as political debates and priorities regarding gender and sexuality have changed over time. In every generation, adults write stories, pen poems, create films, and score songs that fill children’s senses with lasting impressions. Reflecting on “Free to Be’s” legacy, Gloria Steinem remarked, “The children we once were are inside us still…each of us is like a nested Russian doll, with all our earlier selves inside. That’s why grown-up authors can write great children’s stories and why great children’s stories appeal to children of all ages.” By imaginatively conjuring a world—part reality, and in greater part, a utopian fantasy—where “children of all ages” can live authentic, promising lives in a state of relative equality, “Free to Be…You and Me” etched an indelible groove into our nation’s cultural landscape.

This essay was commissioned by the Sound Recording Archives at the Library of Congress.

Jerry Pinkney, Illustration for Free to be…a Family: A Book about All Kinds of Belonging. Courtesy of R. Michelson Galleries, Northampton. © 1987 Jerry Pinkney.