Louder than Words: A History of Wordless Storytelling

The name seems to say it all—it is a book without text where the story is told solely through the art. Images tell the stories and they must be read as carefully as any text. Artists are literally “writing with pictures,” as so aptly phrased by Uri Shulevitz. While similar pictorial choices are made when illustrating books with and without text, in a wordless book the art requires a more intense visual focus on communicating the narrative. Artists create characters personalities through pictures alone, using facial expressions and body language to convey what they may be thinking or feeling. Emotion is also shown through the context of the pictures. The size of an image affects how the reader responds to a character, as does the size of the character within the image, and lighting and color amplify the emotional mood.

The absence of words gives artists complete freedom to design the pages without having to leave space for blocks of text or word balloons. Pages can vary between single-page pictures, double-page spreads, or pages divided into multiple images. Multi-image pages can extend or compress time; a single page of many panels can show scenes across long periods of time, or they can expand a single short moment in incremental detail. The sequencing of the various page layouts creates a visually engaging reading experience. Borders and other design elements are used to visually guide readers through a story and can indicate shifts from reality to fantasy or differentiate between story spaces.

The most radical decision an artist makes is to not use words. When artists remove text, they invite readers to decode the pictures for themselves, so every child reads the book in their own unique way and according to their own personal life experiences and backgrounds. A wordless picture book asks children to collaborate in the storytelling process—a very empowering request.

Beginning in the mid-1960’s, wordless storytelling took hold in children’s publishing. Since that time picture books continue to be the most prolific and creative showcase for wordless stories. Although, with one exception, picture books were late to join the wordless genre.

Stories told only through pictures have been present throughout our history, as evidenced by cave paintings, Greek and Roman pottery, and stained glass windows. These works are often comprised of multiple images working together to tell their stories. In 11th century England there was the Bayeux Tapestry and in 12th century Japan there were Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga (“Animal-person caricatures”), a set of four picture scrolls. Both these works present stories without text and that are read in one direction, showing a specific chronological order. Their images are in sequences that are not divided into individual segments or panels, but are composed in scenes that flow into each other. Wordless narratives are found in almost all art forms, from painting, printmaking, illustrated books, comics, and film—all forms that use images in sequence.

The English painter and printmaker William Hogarth may be the only example of both a wordless and sequential storyteller in fine art until the 20th century. In 1731 Hogarth created a series of six paintings called A Harlot’s Progress in which the pictures are read in sequence from left to right. The images are dense with detail and must be examined closely to absorb all the nuances of the tale as the characters react to each other and to their surroundings. Hogarth, a skilled engraver, created sets of prints of his paintings to sell. The prints were so popular that he may have invented another concept—the sequel. A Rake’s Progress followed in 1733 and the two sets of prints were so successful that new copyright laws were created to combat the host of knockoffs that hit the market.

In the 1800’s, several new visual narrative mediums developed that explored their forms without words. In Japan, a new form of sequential picture making called Manga (“impromptu drawing”) appeared from artists such as Santo Kyoden, Aikawa Minwa, and Katsushika Hokusai. Swiss teacher and author Rodolphe Topffer published “picture stories” that put words and pictures into sequential panels. Topffer’s stories paved the way for the modern comic strip. In the 1870s and 1880s, Randolph Caldecott in England coined the phrase “picture books” to describe the children’s books he created. He was the first to put pictures on every page, and made the images as integral to the story as the text. And motion pictures were invented.

Initially movies were silent, not by choice, but because the technology had not been invented to include sound. They were not really silent either, as musical accompaniment was a part of the movie-viewing experience. And they were not strictly wordless, as directors used title cards to convey some of the dialogue. However, the main way the stories were conveyed was through visual imagery, and through the most radical part of filmmaking, editing. The juxtaposition of one shot in a film—or one picture in a book—next to another creates a narrative. The viewer or reader must mentally make the connection between the two. Editing is the essence of visual storytelling whether on screen or in a book.

The limitation of working without recorded sound became the early movies’ greatest attribute. Filmmakers like Fritz Lang, F.W. Murnau, Charlie Chaplin, and Buster Keaton found extraordinary ways to tell stories visually. There are many, like Chaplin, who believed that the 1910’s and 1920’s produced the most visually inventive films ever made.

Movies had a dramatic effect on many graphic artists who sought to capture on the page the movement and excitement of motion pictures. Nobel laureate author Thomas Mann claimed that Passionate Journey was the movie that impressed him the most. Yet Passionate Journey was not a movie; rather, it was a wordless novel published in 1919 by Belgian artist Frans Masereel. Masereel was a political cartoonist and printmaker who worked in a bold, expressionist style that lent itself perfectly to the woodcut prints he made to comment on social issues like the First World War and the industrialization of society. He decided to tell stories using his prints, in the form of books. And, in a stroke of genius, he chose not to include any text. Passionate Journey and Masereel’s other wordless books essentially birthed the genre of what we now call the graphic novel. In his lifetime, he published over fifty wordless books.

Masereel inspired other artists to create their own wordless novels. In the late 1920s and early 30s, Otto Knuckel, Helena Bochorakova-Dittrichova, Giacomo Patri, and Lynd Ward all produced wordless books with woodcuts after seeing Masereel’s. In 1934 the German painter Max Ernst collaged illustrations from pulp novels and encyclopedias to create the surrealist wordless novel Un Semaine du Bonte. American Lynd Ward became the most well-known maker of wordless woodcut novels in the United States. His first publication, God’s Man (1929), was a success and he produced five more wordless novels over the next eight years.

Several comic strip artists also made the leap into book length narrative via the wordless novel, using pen, brush, and ink rather than woodcut. William Gropper published Alay-oop in 1930 and Milt Gross lampooned the wordless novel genre with He Done Her Wrong, also in 1930. Myron Waldman, an animator for Max Fleischer’s studios, published his wordless novel Eve in 1943.

Other artists stayed within the world of newspaper comics to produce wordless stories, although there are only a few examples. The most imaginative of these strips was Polly and Her Pals by Cliff Sterrett, which debuted in 1912. In the first half of the 20th century, Sunday comics such as Little Nemo, Krazy Kat, and Gasoline Alley took up an entire page of a newspaper, a remarkable showcase for their art. Like the others, Polly and Her Pals had a “topper” strip, which was a separate, shorter story that ran above the main comic. Sterrett’s top strip, Dot and Dash, about a pair of dogs, was always wordless. The rest of the page featured the adventures of Polly, which was regularly wordless. Sterrett used elements of cubism and surrealism, making his comic strip one of the most visually exciting. The other wordless strips were Otto Soglow’s The Little King, premiering in 1934, and Carl Thomas Anderson’s Henry, which began in 1932.

All this wordless activity did not last. Sound entered movies in the late 1920’s and after the release and huge success of the “talkie” The Jazz Singer in 1927 there was no turning back. By 1930 almost all films included sound, although purist Charlie Chaplin held out until 1936 when he released his last silent film, Modern Times. Over the years there has been the occasional film made without dialogue, like The Thief in 1952, staring Ray Milland; Albert Lamorisse’s The Red Balloon in 1956; Chantal Ackerman’s Hotel Monterey in 1973; Michael Hazanavicius’s The Artist in 2011; and The Red Turtle, by Michael Dudok de Witt in 2016. But these are anomalies measured against the vast numbers of movies released each year.

After their heyday in the early 1930s and early 40s, wordless graphic novels were produced only occasionally. While there were notable works by Laurence Hyde (Southern Cross), Eric Drooker (Flood! and Blood Song), Peter Kuper (The System), Jim Woodring (The Frank Book), and others, they are small in number within the graphic novel genre.

In newspaper comic strips, Polly and Her Pals, The Little King, and Henry remained the only wordless examples up until they ceased publication, Polly in 1958 and the other two in the 1970s. Henry expanded into comic book form in the 1940s and dialogue was added, although the daily strip remained silent. There are scant few examples of wordless stories in the world of superhero comic books.

This brings us to picture books. The 1930’s were, to quote historian Leonard Marcus, “when the American picture book came of age.” (I highly recommend Marcus’ essay for The Carle’s 2019 exhibition Out of the Box: The Graphic Novel Comes of Age, which dovetails with much of this essay). In 1931 Helen Sewall’s picture book, A Head for Happy, was published. It is not a wordless book, but it’s close. The text is minimal and many of its 64 pages are without words, including several double-page spreads. There is just enough text though that I don’t categorize it as a wordless book.

In 1932 Macmillan published What Whiskers Did, a picture book by author and artist Ruth Carroll. Drawn in black crayon, it tells the story of Whiskers, a Scottish terrier that gets loose from a young girl and runs into the woods. There the dog encounters a rabbit and then a fox. Fleeing the fox, Whiskers and the rabbit escape down a rabbit hole.

These scenes are rendered realistically, but in echoes of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, the trip through the rabbit hole changes the story from realism to fantasy as the animals become anthropomorphized. Whiskers dines at a table with the rabbit family and uses utensils. They play games, including blind man’s bluff. When it is time for Whiskers to leave, he bids the rabbits goodbye and returns to the little girl, who is thankful her dog has come home. This is the first completely wordless picture book published in the United States. Incredibly, it will be thirty years before there is another. That gap is still a mystery but, in contrast to comics, graphic novels, and film, once children’s publishers began producing more wordless picture books, they became the art form where wordless storytelling flourished like no other.

What Whiskers Did appeared the same year as Lynd Ward’s wordless novel Wild Pilgrimage, the comic strip Henry launched in newspapers, and a year after Chaplin’s silent film, City Lights. Why did Ruth Carroll choose to make her book wordless? Was she inspired by the wordless stories in those other mediums? Louise Bechtel was editor of Macmillan’s children’s book department at the time and had published A Head for Happy a year before. She was an innovative and forward-thinking editor. Did she influence Carroll’s decision? Did she and/or Carroll look at A Head for Happy and think, “well, why use any text at all?” I haven’t yet found any research to shed light on the genesis of Whiskers, but given the amount of other wordless material in print at that time, it isn’t surprising there would be a wordless picture book too. The question is not why was there a wordless picture in 1932, but why, and for so long, was there only one?

My own first introduction to wordless stories came from a Giant Golden Book my family owned, The Provensen Animal Book, published in 1952. It contains a wide range of material, from poems and short stories to visual puzzles. On one double-page spread the Provensens present three “stories without words.” They are very simple, only three to six panels each, but I can vividly recall how captivated I was by these little vignettes.

In 1954, Max, by Pericle Luigi Giovannetti, was published. Giovannetti was a painter and illustrator who drew cartoons for the British satirical magazine Punch, where he created the character of Max, a marmot that engages in pantomime slapstick adventures. Macmillan compiled and published many of those drawings in book form in the U.S. Max was also published by others around the world. There is no through-line narrative; the book is essentially a collection of stand-alone cartoons that appeal to all ages. Other Max books followed in the next few years.

In 1960 Alfred A. Knopf published I Am Andy, by Charlotte Steiner. It was marketed as a “You-Tell-A-Story Book.” Each double-page spread contains five or six vignettes, or panels, showing Andy involved in a particular activity. A preamble states, “You can tell the stories in your own words.” It’s too bad that each spread has a title such as Andy Plays the Trumpet and Andy and the Cat. Those titles are a bit of a deal breaker for me.

There are no wordless picture books in 1961, but in 1962 Tomi Ungerer came out with Snail, Where Are You? This is a wonderful book made by a great artist who had already made great picture books with text. Snail is conceptually simple and elegant, with beautiful and witty drawings that incorporate the spiral of a snail shell into each picture. That’s it. Ungerer allows readers to see the relationship between shapes and objects. It is a book that asks us to look closely at the pictures and at the world around us. There is a line of text at the end, “Snail, where are you?” that is answered on the last page by the snail, “I am here.” That text is a funny little ending, but is in no way integral to what the pictures have done in the previous pages. To me, Ungerer’s book marks the date when wordless picture books begin to really take off.

While in 1963 three more wordless books are published, it was the release of Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are that is perhaps more notable when it comes to wordless storytelling. Although not wordless, the book contains three consecutive wordless double-page spreads that encompass the Wild Rumpus and that exposed millions of readers to the idea of “wordlessness.” There are two more wordless picture books in 1964, including another by Tomi Ungerer, One, Two, Where’s My Shoe?

There is one wordless picture book in 1965—What Whiskers Did. Yes, Ruth Carroll’s book again! Thirty-three years after the first edition, Carroll completely re-illustrated the book. Instead of the original Scottish terrier, it now stars a poodle and contains a single brown color overlaid on the drawings. I’m again curious about Carroll’s motivation. There were only a few other examples of wordless picture books, so why did she and the publisher think the world was ready for a second version of Whiskers? Perhaps they were right, since two years later Scholastic released a paperback edition of Whiskers and Carroll would publish five more wordless books in the late 1960s and 70s.

The year 1966 saw one wordless book, but in 1967 there were six. In 1968 there are again six, and in 1969 there are fourteen. From there the numbers continue to rise to a peak of 67 books in 1986 before trending back down to twelve in 1991. Despite the dropping numbers, wordless picture books continued to be published thereafter, some to great popularity and others to great acclaim (and sometimes both), winning major prizes in the field.

As the numbers of wordless picture books began to rise, many were one-time explorations by their author/artists. For others, the idea of text-free stories was something that resonated deeply and they created wordless books as a major part of their careers. Beginning in the late 1960s and early 70s, that latter group includes author/artists such as Mercer Mayer, with his popular Boy, Dog, and Frog series; Mitsumasa Anno and his remarkable Journey books; Fernando Krahn, who made over 20 very funny wordless books; and Tana Hoban, a photographer who created dozens of beautiful concept books that invite readers to look intensely at the world around them.

In 1968 John S. Goodall created the first of many wordless picture books with The Adventures of Paddy Pork (which won the Boston Globe-Horn Book Award). Paddy Pork is a “moveable book,” a book that utilizes pull-tabs, flaps, and other interactives. Most of Goodall’s books contain an extra half page, or flap, in the middle of each double-page spread. When the book is open with the flap laying flat on the right-hand side, the reader sees a full double-page image. When the reader turns the flap, it reveals the same scene but with the characters in different positions. The flap acts as a form of animation, adding the element of time to the story.

Lynd Ward, one of the founding fathers of adult wordless novels, also had a long career in children’s books, winning the 1953 Caldecott Medal for The Biggest Bear, a book he also wrote. In 1973, at the end of his career, he finally created a wordless picture book for children, The Silver Pony. In contrast to the woodcuts he used for his adult wordless novels, for The Silver Pony, Ward painted the pictures in black and shades of gray.

In 1978 Peter Spier was awarded the Caldecott Medal for Noah’s Ark, the first wordless book to win the medal. Spier created several other wordless books, including Rain (1982), a book that, like Noah’s Ark, uses a wide range of page designs: full-page images, double-page spreads, and pages divided into multiple panels. The effect creates a wonderfully varied reading experience and is anything but static.

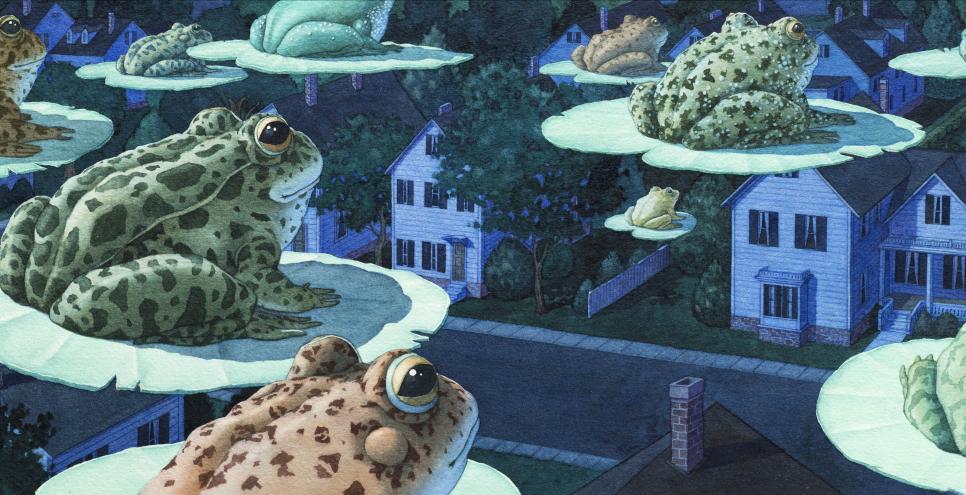

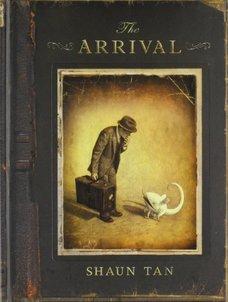

Raymond Briggs took a similar approach to page design in The Snowman, published in 1978. The Snowman is one of the best-known wordless picture books, helped in part by its popular 30-minute animated film adaptation released in 1982. Briggs’ design of The Snowman served as inspiration for artist Shaun Tan when he created his epic wordless book, The Arrival (2007). Like Briggs and Spier before him, Tan uses multi-panel designs to tell his story, although he goes much farther. Some pages have four or five panels, while others have as many as sixty. With so many panels Tan shows complex actions in great detail.

Year after year picture books artists continued to be drawn to wordless storytelling. Peter Spier moved back and forth between books with text and books without, as have many other artists including Emily Arnold McCully, Tomie dePaola, Jeannie Baker, Peter Sis, Suzy Lee, and myself. Most, but not all, of Arthur Geisert’s books are wordless. Barbara Lehman and Aaron Becker work exclusively in the wordless realm.

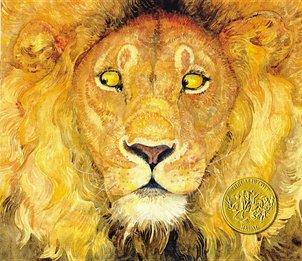

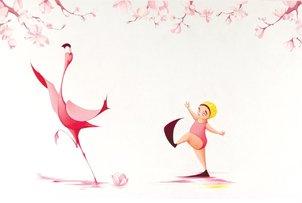

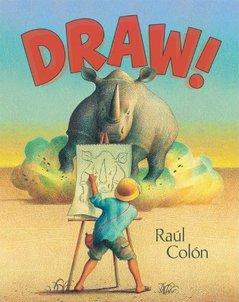

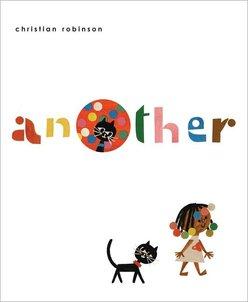

In innovative, yet unique ways, Jorg Muller, Istvan Banyai, and Laetitia Devernay expanded the definition of design in their wordless books. Donald Crews and Christian Robinson use flat graphic images, while Eric Rohmann and Marla Frazee illustrate rich and lush images. Molly Bang creates mystery through the use of positive and negative spaces, and Raul Colon changes his artistic style to move in and out of fantasy. Issa Watanabe and Henry Cole have made intensely emotional wordless books, while JiHyeon Lee’s and Stephen Savage’s books are whimsical and funny. Molly Idle continues John S. Goodall’s tradition of moveable wordless books with her ingenious use of flaps in Flora and the Flamingo (2013).

I’ve focused mainly on publishing in the United States, but wordless picture books are a global phenomenon. Referred to as silent books in some other parts of the world, they are extraordinary and deserve an exhibition of their own. A great resource for these books can be found on the website of the International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY).

There is so much more to explore regarding wordless picture books: the role of editors in the decision to take a wordless approach to a story; the reluctance of many adults to buy wordless picture books for fear of not knowing how to read them to their children; the fascinating research showing how wordless picture books generate expansive use of vocabulary during parent child reading; and the inspiring ways teachers use wordless picture books to release the imaginations of all students, and to help those struggling with English as a second language, dyslexia, and other learning issues.

For now, let’s just focus on the art. What we see in this exhibition is how artists have created remarkable visual reading experiences. By making the decision to remove words, the artists pare their books down to the essence of their art—the pictures—and leave those pictures open to interpretation. In doing so the artists invite children to make the stories their own.